On October 9th, 2022, an unusually bright pulse of high-energy radiation whizzed past Earth, captivating astronomers around the world. The luminous emission came from a gamma-ray burst (GRB), one of the most powerful classes of explosions in the universe. Named GRB 221009A, it triggered detectors at NASA’s Gamma-ray Burst Monitor and Large Area Telescope (both on board the Fermi Gamma-ray Space Telescope), the Neil Gehrels Swift Observatory, and the Wind spacecraft as well as other telescopes that quickly turned to the GRB site to study its aftermath.

This record-shattering GRB is one of the closest and the brightest GRB ever spotted, earning it the nickname BOAT (“brightest of all time”). This GRB is believed to come from an exploding star and likely signals the birth of a black hole.

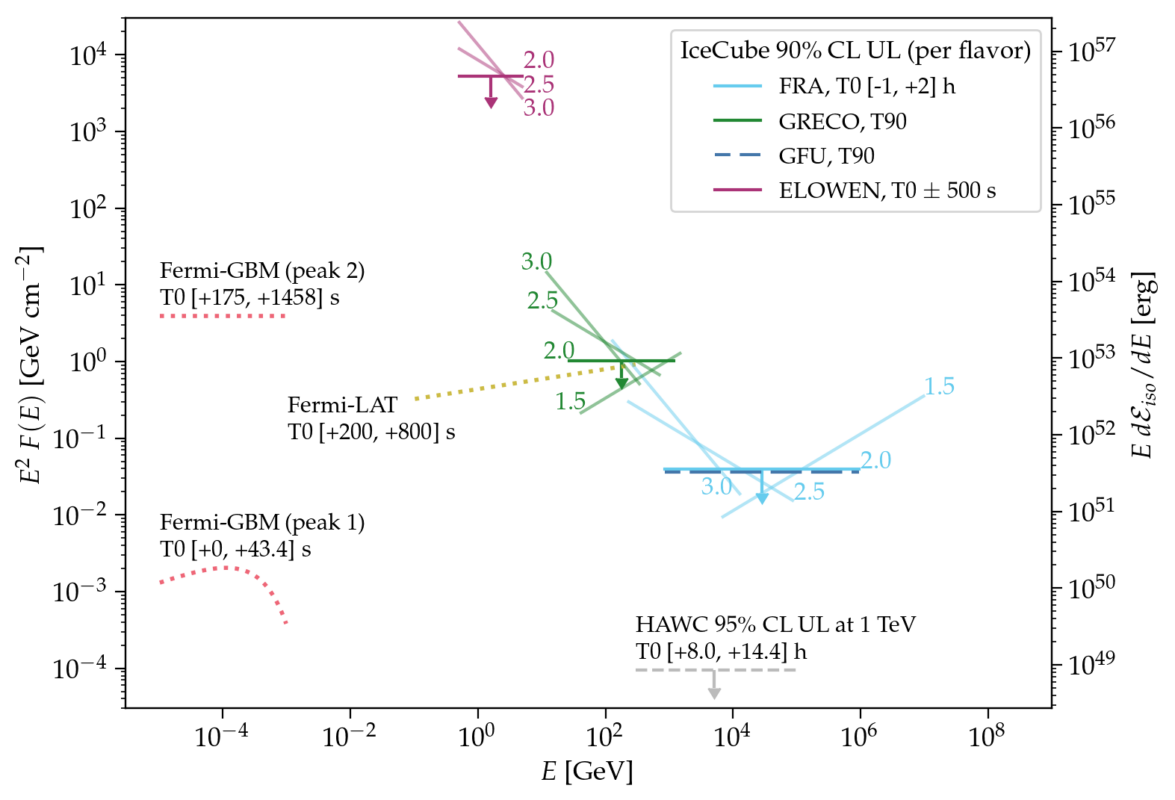

In a new study by the IceCube Collaboration, published today in The Astrophysical Journal Letters, UW–Madison researchers presented results of one of five searches for neutrino emission from GRB 221009A that leveraged the full detector range, covering nine orders of magnitude in energy. Because no significant emission was found across samples spanning 10 MeV to 10 PeV, the results are the most stringent constraints on neutrino emission from GRBs.

As some of the most energetic sources in the universe, GRBs have long been considered a possible astrophysical source of neutrinos—tiny “ghostlike” particles that travel through space and large amounts of matter unhindered. These high-energy neutrinos are of particular interest to the National Science Foundation-supported IceCube Neutrino Observatory, a gigaton-scale neutrino detector at the South Pole.

IceCube is run by the international IceCube Collaboration, which comprises over 350 scientists from 58 institutions around the world. The Wisconsin IceCube Particle Astrophysics Center (WIPAC), a research center at UW–Madison, is the lead institution for the IceCube project.

Previously, IceCube has performed searches for neutrino emission from GRBs, but thus far, a correlation has not been found between high-energy neutrinos and GRBs. The recent observation of GRB 221009A presented IceCube with the best opportunity yet to search for neutrino emission by GRBs.

“Not only was this GRB the brightest ever detected in gamma rays, it also occurred in a region of the sky where IceCube is very sensitive,” says UW–Madison physics professor Justin Vandenbroucke, who helped lead the analysis.

For the study, collaborators carried out five complementary IceCube analyses that encompassed the full energy range of the detector. Each analysis targeted a specific energy range, with the idea of covering as wide an energy range as possible. UW–Madison physics PhD student Jessie Thwaites was one of the main analyzers.

Thwaites performed a “fast response” analysis based on real-time data from the South Pole to search for high-energy (0.10 teraelectronvolts to 10 petaelectronvolts) neutrinos from the direction of the GRB. They chose two time windows: one three-hour window covering all of the triggers reported in real time, and one covering two days. Their analysis, which set strong constraints on neutrino emission from GRBs, was quickly reported to the community, within hours of the GRB being detected by the gamma-ray satellites.

“In the high energies, our upper limits are very constraining—they are below the observations from gamma-ray telescopes,” says Thwaites. “These upper limits, combined with the observations from many electromagnetic telescopes, give us more information about GRBs as potential particle accelerators.”

Because this GRB is so bright, and because it has been so well studied, IceCube is able to place constraining upper limits on neutrino emission models proposed for this specific GRB. These constraints will enable better understanding of how GRBs work.

The collaborators are already developing new methods to improve searches for neutrinos from GRBs and other transient astrophysical sources. In addition, future upgrades and proposed extensions of IceCube, including the IceCube Upgrade project and IceCube-Gen2, could be the key to finding high-energy neutrino emission from GRBs or other transients.

According to Vandenbroucke, “This GRB illustrates the capabilities of IceCube for real-time follow-up of astrophysical transients. IceCube views the entire sky, all the time, over a factor of a billion in energy range. There is likely a burst of neutrinos already flying towards us from some other cosmic source, and we are ready for it.”

+ info “Limits on Neutrino Emission from GRB 221009A from MeV to PeV using the IceCube Neutrino Observatory,” The IceCube Collaboration: R. Abbasi et al., ApJL 946 L26 (2023), https://iopscience.iop.org arxiv.org/abs/2302.05459