Since November of last year, a team of IceCube engineers and scientists have been hard at work during the second of three consecutive field seasons for the IceCube Upgrade. Over the course of the season, 37 team members, including 27 drill engineers and 10 installation and operations experts, were deployed to the U.S. National Science Foundation’s Amundsen-Scott South Pole station, with a maximum of 30 people at any given time. The project is funded by NSF and international collaborators.

Each field season was more like a 10-week sprint, with a productive first field season last year setting up the project for success. The goal of the Upgrade is to drill seven holes next year and deploy seven more closely spaced and more densely instrumented strings of optical sensors in the central part of the array, which will improve IceCube’s sensitivity to low energies.

The majority of the team’s engineers come from the University of Wisconsin–Madison’s Physical Sciences Laboratory (PSL), where drill and installation equipment has been fabricated and shipped to the South Pole. Additional drill engineers hail from Sweden, Taiwan, and Thailand. Installation experts came from Germany, Australia, the US, and Japan.

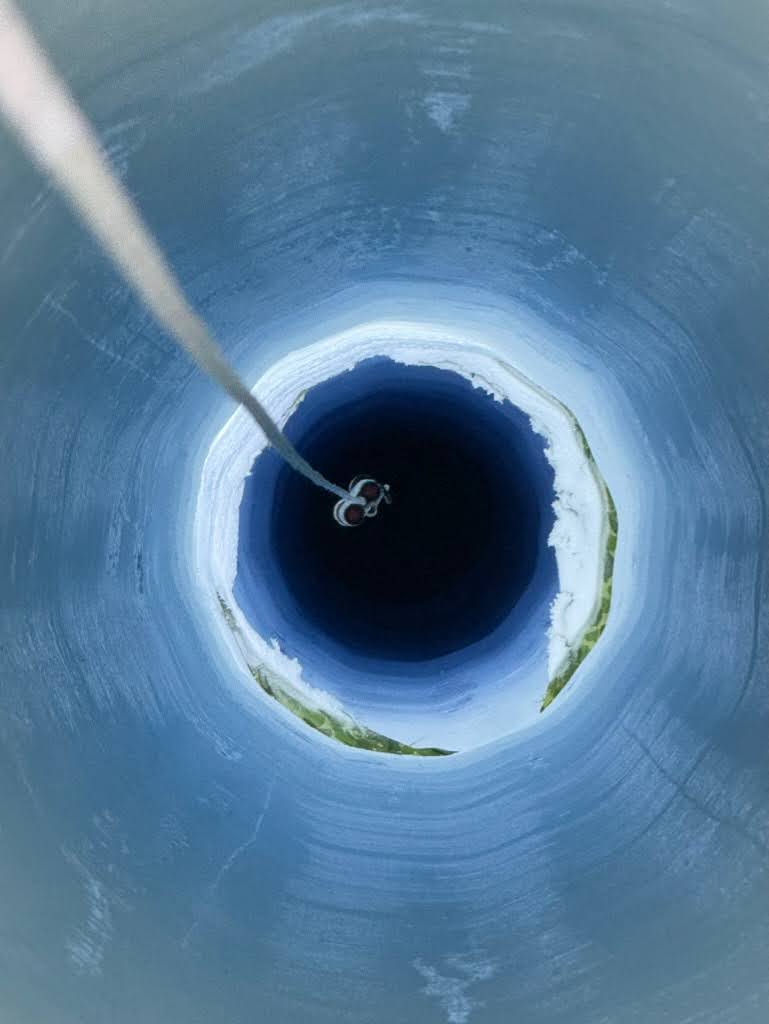

Last season was focused on performing repairs of the drill and setting up the drill camp, which had not been used since the completion of IceCube in 2011. This season, the focus was on 1) commissioning the main hot water drill, 2) drilling through the firn—the intermediate layer between snow and glacial ice—for the seven Upgrade holes that will be drilled during the final season, 3) testing two strings of new optical modules, and 4) installing the readout systems and cables for the seven Upgrade strings.

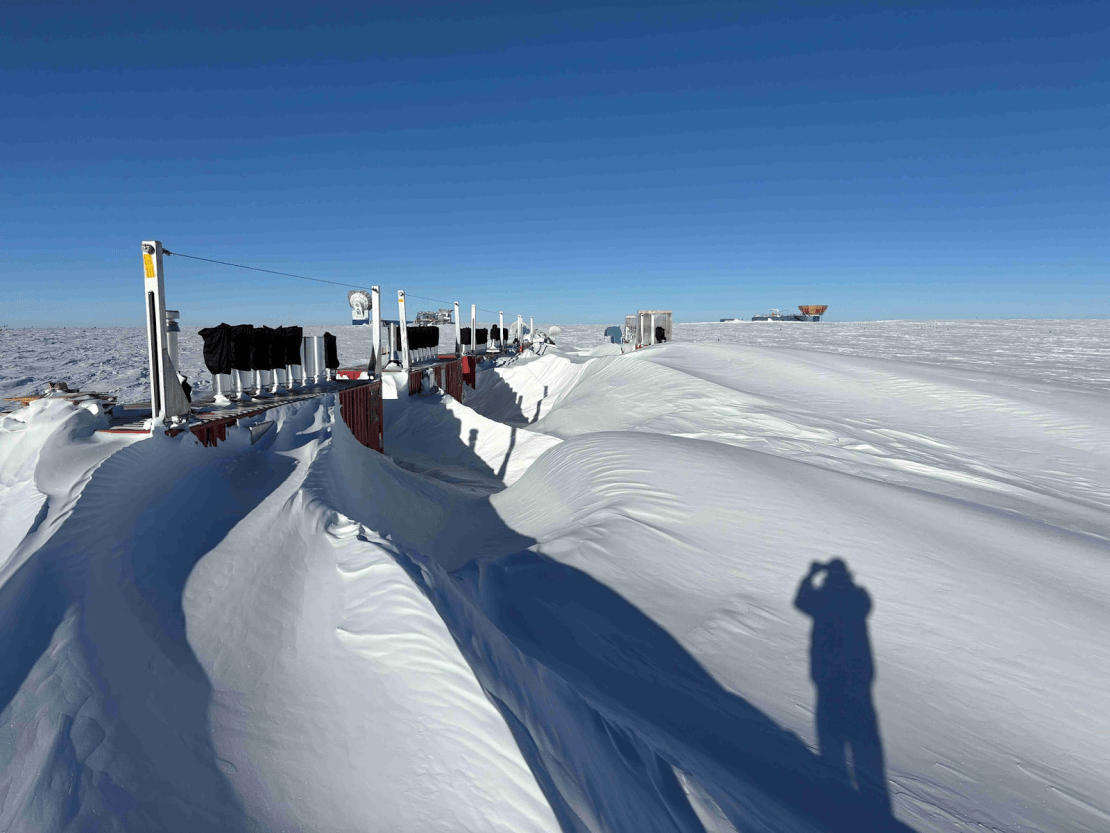

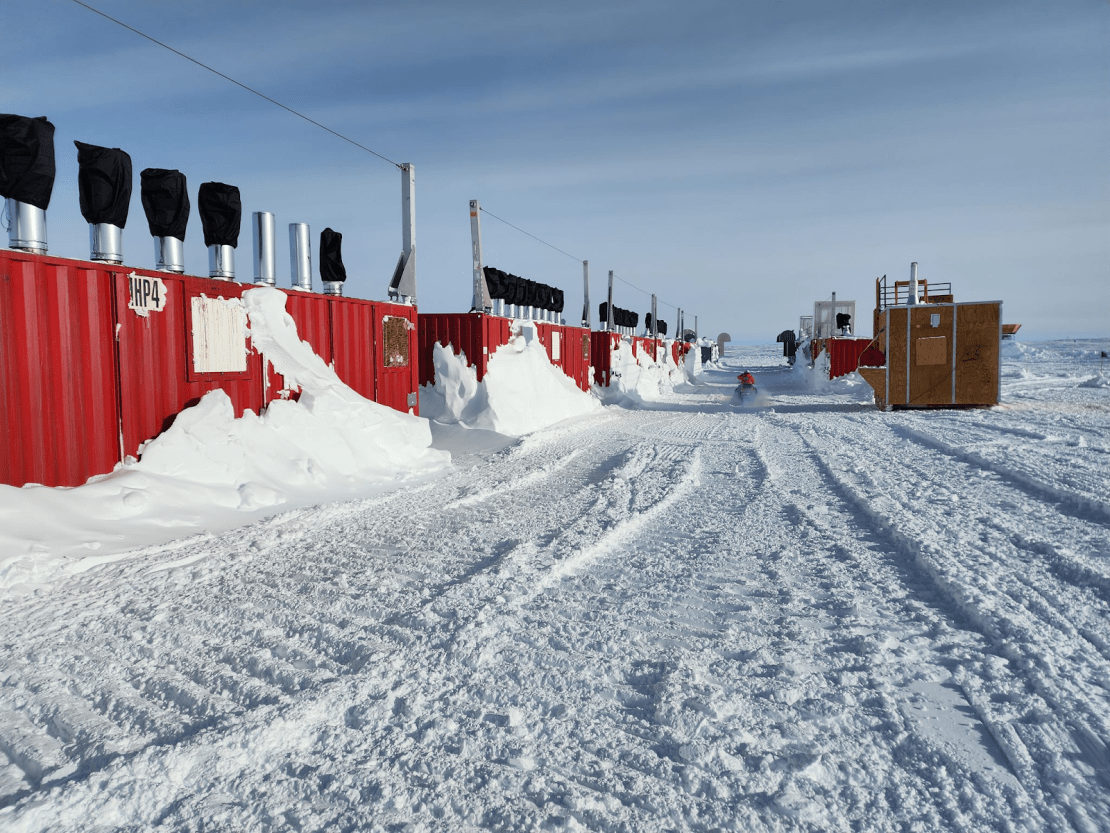

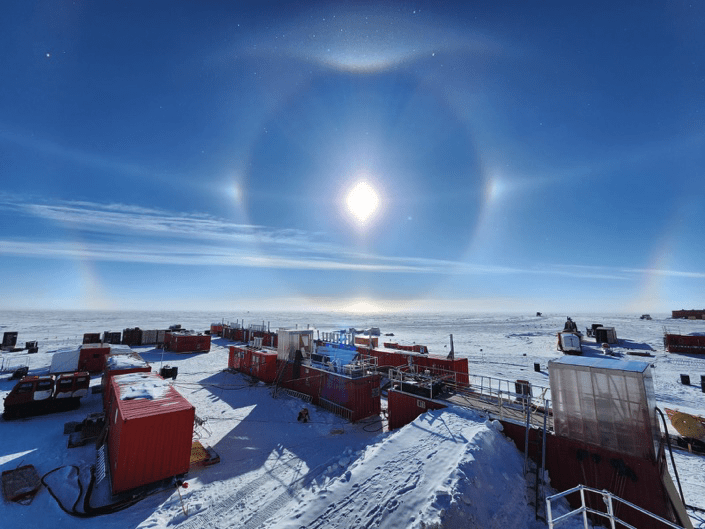

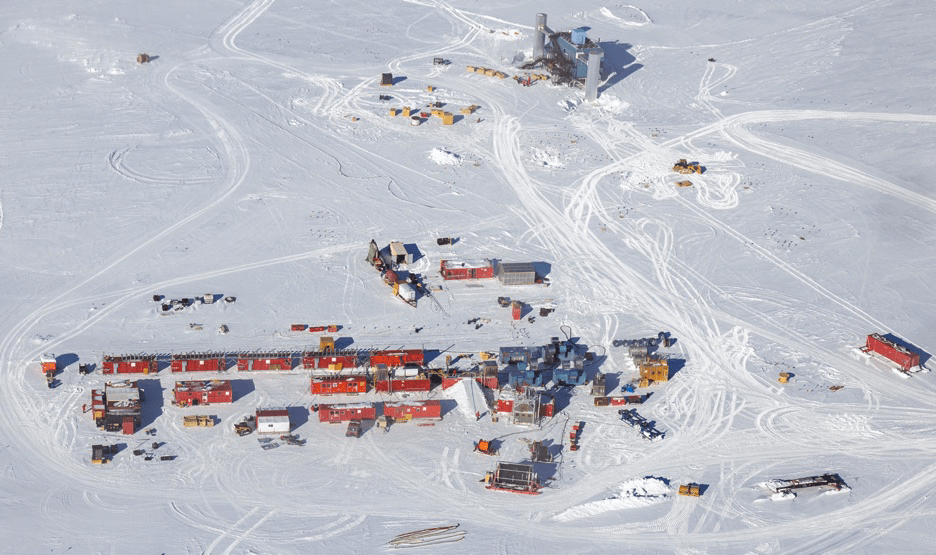

During the first month, the Upgrade team spent time digging out the drill camp near the IceCube Laboratory (ICL), along with getting the generators up and running to deliver heat and electricity to the buildings. The major priority this year was integrating the largest hot water drill system in the world, with the 5-megawatt hot water drill system consisting of 40 mobile buildings. When fully operational, the drill will be used to make the Upgrade holes next season, requiring 28 crew members working around the clock, with a single 2.6-km hole taking about 50 hours to complete.

Linnea Avallone (NSF’s Chief Officer of Research Facilities) stand in front of the hose reel that has been fully loaded with the hose required to drill the seven Upgrade strings next season. Credit: Albrecht Karle, IceCube/NSF

“It was exciting to see the many pieces of the world’s most powerful hot water drill come to life as a functioning system,” says Albrecht Karle, the principal investigator of the Upgrade. “The expert team showed incredible commitment working six-day weeks for almost three months under harsh conditions on the ice. As a result, we are set to come back at the end of the year, and, after years of preparation, commence the installation of 700 high-performance instruments in December.”

In addition to the main hot water drill, an additional independent firn drill is used to get through the initial softer mixture of snow and ice. This season, the crew drilled the firn holes for all seven Upgrade strings in preparation for continued drilling of all seven holes next season.

The Upgrade strings will feature new optical sensors, the multi-PMT digital optical module (mDOM) and the “Dual optical sensors in an Ellipsoid Glass for Gen2,” or (D-Egg). The team received and successfully tested the first 200 (out of 700) of these optical sensors (enough for two strings) to ensure readiness in December when they will be deployed.

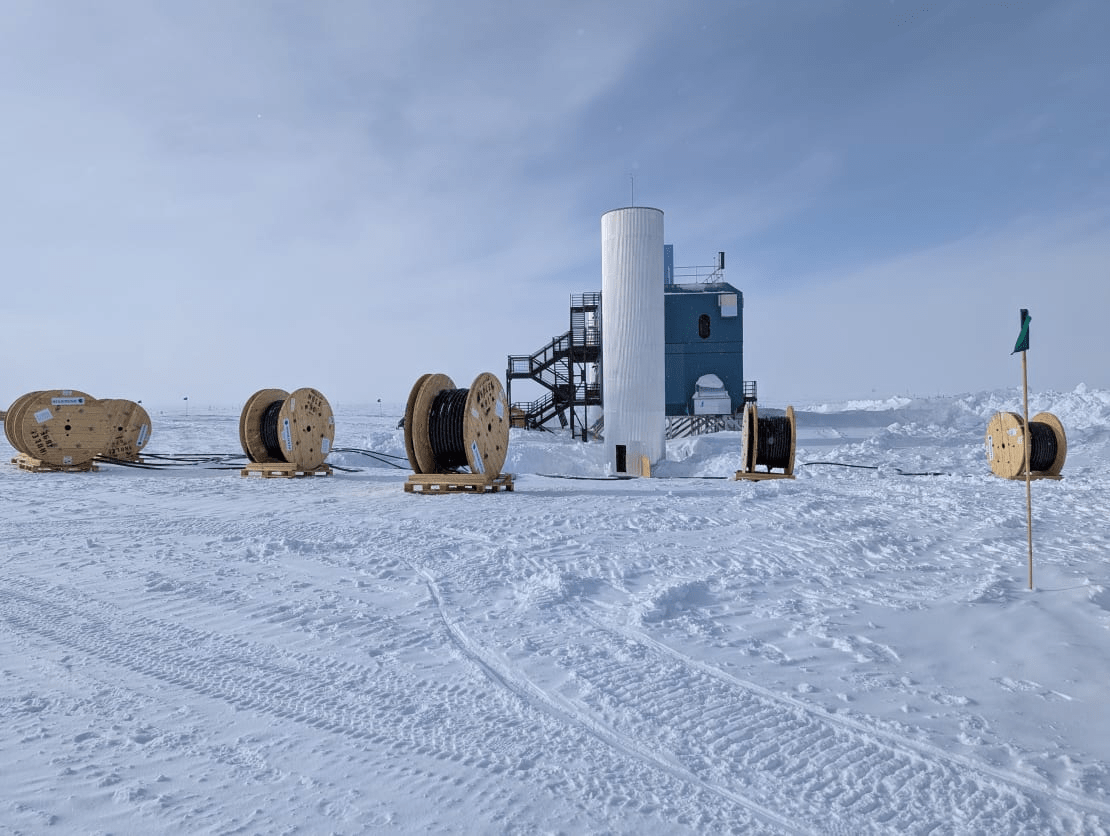

“The success of the Upgrade relies on the strength of the IceCube Collaboration. Major contributions came from our international colleagues in Germany and Japan, who contributed optical sensors, and Sweden, who contributed surface cables. In the US, Michigan State University contributed the main cables and is one of the sites for building and testing optical modules,” says Vivian O’Dell, the project director for the IceCube Upgrade and the planned extension of IceCube, IceCube-Gen2.

IceCube scientists also view the Upgrade as a stepping stone to IceCube-Gen2.

“This upgrade will enable us to record 100,000 neutrinos annually and measure their properties, an incredible number for a neutrino detector,” says Karle. “Neutrinos are the least understood known subatomic particles. The new detector in the center of IceCube will allow us to measure their properties with unprecedented precision.”

Another big success this season was pulling all seven Upgrade surface cables up the tower and into the ICL, a complex operation that required all hands on deck.

At the end of the season, the seasonal equipment site (SES), which provides a stable supply of electricity and hot pressurized water throughout each field season, was successfully tested at full capacity with high temperature, high pressure, and high water flow.

“Plans for this season were ambitious and had a lot of moving parts,” says Terry Benson, the director of PSL. “Watching the IceCube team and the Antarctic Support Contract coordinate and work together to check off major milestones week after week was truly inspiring.”

The team prepared for the final field season by winterizing the equipment, which entails storing sensitive components in special heated areas to survive the cold winter months. Just last week, the final IceCube team members left the ice, with some headed back home and others on vacation at a much warmer place.